Advocacy Project

What is the Advocacy Project?

The advocacy project is a research project spanning several weeks, which addresses the increasing prevalence of owl suffering and death caused by anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning.

I utilized a multimedia approach: combining social media advocacy (Twitter) with writing based on scientific research articles.

Below is the culmination of my efforts to define the owl, define the problem it faces, and define long-term solutions.

Second-Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticide Exposure in Owls

A Barn Owl glides above the forest floor, its wings making little more noise than a whisper. Below, a bold mouse takes a daring risk, attempting to cross out in the open. Utilizing a combination of noise-dampening feathers, eyes designed to see minute details in darkness, and pinpoint accurate hearing, the owl knows exactly where the mouse is, and the mouse is none the wiser. It silently banks around a tree, swoops down, and snatches tonight’s dinner with razor-sharp talons. Rodents can do little when faced with a predator that has evolved to become the apex nocturnal hunter (Sieradzaki).

Owl Overview

Owls are nocturnal birds of prey who spend most of their time hunting for food to feed themselves and their young. Most owls are carnivores, therefore they’re optimized to hunt small mammals and other animals including rodents, voles, frogs, lizards, snakes, fish, rabbits, birds, squirrels, other owls, and other creatures (Owl Research Institute).

Like many birds of prey, their eyes are designed to collect vast amounts of visual information. Their large, forward-facing eyes provide binocular vision, providing accurate depth perception. Unlike other birds of prey, owl eyes contain a higher quantity of rod cells, which are retinal cells responsible for detecting motion and visual information on the black to white scale. (Borges et al.) Furthermore, their eyes are relatively large compared to their body.

Masters of Acoustic Perception

Although owls have notable visual capabilities, their strengths lie in their command of the sound environment. Owls have specialized ears designed to detect any sound their prey can make, containing significantly longer cochlea (the main hearing organ) than other birds. Their ears are asymmetrically situated to enhance sonic accuracy, and their recognizable disk-shaped faces serve as parabolic sound amplifiers, guiding quiet sounds to their ears.

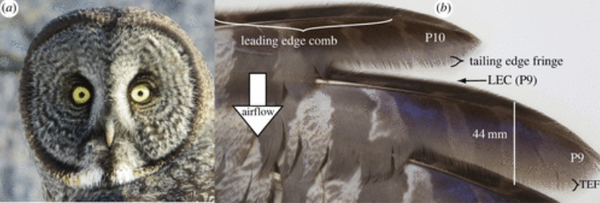

In 2011, scientist Christopher J. Clark and his colleagues published a study providing insight into the incredible hearing abilities of the Great Gray Owl. They wanted to determine how this owl hunts prey it cannot see using sound alone, specifically how it overcomes confusing sound cues to accurately locate prey.

Experiment: How well can Owls hear through Snow?

To examine the extent to which the Great Gray Owl can hear sound through a physical medium, Clark and his colleagues placed a speaker several inches deep in snow and played sounds that mimicked a vole tunneling through the snow. This speaker attracted a Great Gray Owl to attack the speaker, allowing the researchers to determine the sound aspect of this owl’s hunting environment.

Using an acoustic camera, scientists determined that sound refraction (the sound source is perceived to be elsewhere than it actually is) occurs when an owl isn’t directly above a sound source, feeding the owl an acoustic mirage rather than the actual location of its prey. (Clark et al.)

How does the Great Gray Owl accurately detect prey? An owl initiates an attack from distances that can distort accurate auditory cues. Therefore, the owl has to interpret real-time audio cues to rapidly adjust its course from point (a) to point (b). At point (c), the owl utilizes its silent feathers and large facial disk to both mask its flight sound and to pinpoint exact prey location.

The owl’s trajectory of attack ends in a hovering phase, where the owl prepares to dive for its unsuspecting prey.

The Great Gray Owl’s uniquely large facial disk is uniquely adapted to hearing lower frequencies compared to Barn Owls, who rely on higher frequencies to locate prey. (Payne) Moreover, compared to all other birds, the Great Gray Owl has the most effective adaptations for flying silently, especially when hovering over prey. Not only do prey animals fail to hear the owl, but the owl can hear more since it makes less flight noise. Therefore, this owl is an ideal snow hunter, able to hear a vole or mouse tunneling under up to 18 inches of snow (Clark et al.).

Camouflage

Owls have more feathers than any other birds, including feathered eye outlines and sometimes feathered feet/toes. The color of their feathers, including soft browns, greys, black, and white, serve as natural camouflage by breaking up their outline when compared to the background (Sieradzaki).

Examples of owl camouflage.

Vocal Distinction

Owl hoots are among the most distinctive bird sounds. “Hoots are very individual to the bird. Every owl has a signature hoot, kind of like a fingerprint, and that allows them to identify their neighbors, their mates, their allies, and also allows us to identify individual owls in the wild,” says Jennifer Ackermann, author What an Owl Knows. “They have greeting hoots and territorial hoots and emphatic hoots” (What an Owl Knows).

Their expressive repertoire isn’t limited to just hoots. Jennifer tells us that owls “chitter, squawk, squeal, and their different calls communicate really highly specific information about their sex, their size, their weight, their individual identity, and even their state of mind” (What an Owl Knows). Machine learning analysis of owl vocalizations has revealed that adult owls can recognize individual hoots. If researchers can recognize individual territorial hoots, they can more accurately monitor owl populations, which is an important conservation tool.

So What?

Engineers and researchers, intrigued by the mechanisms behind owls' silent flight, seek to replicate these principles in the design of quieter aircraft and drones. What scientists learn from the silent design of an owl’s feathers can be applied to noise pollution reduction projects, such as reducing jet roar from turbulence and reducing wind turbine noise. Unfortunately, airplane wings and owl wings are structurally different. (Smithsonian Magazine) Furthermore, owl biology could prove models for advancement in hearing aid technology and improvements to sound localization algorithms.

Why care about owls?

The most important reason to care about owls is that they occupy an exceptional ecological niche in their environment as population control. Under cover of darkness, their prey can neither see nor hear them coming, cementing them as apex predators in their respective ecosystems.

Although an owl's work is mostly done unseen, their absence has visible impacts. When an apex predator population declines, prey populations (rodents, in this case) increase unchecked. This upsets the natural balance, something humans already do frequently.

As the barn owl devours the rat whole, it unknowingly consumes more than a hearty meal. This rat has recently consumed an eventually lethal dose of anticoagulant rodenticides, and the barn owl will absorb some of this harmful toxin. When it arrives back at the nest, the barn owl regurgitates the rat for its owlets, unknowingly feeding them harmful anthropogenic chemicals. Over the next few months, this barn owl will consume more poisoned rodents, which will cause the owl secondary poisoning and internal bleeding, putting it in a weakened state and decreasing its survival odds. Eventually, this barn owl dies of internal bleeding, one of many owl corpses piling up as a result of rodenticide exposure.

Second-Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticide Exposure in Owls

Imagine that every piece of food you ate contained small amounts of poison as a result of someone else’s negligence and unwillingness to care more about not accidentally contaminating your food. They know that this poison gradually accumulates in your body until it eventually kills you, poisoning your loved ones in the process. Yet they don’t make the effort to do something about it. This is the worldwide situation owls face.

Background/Overview

Owls are important components of food webs across the world. They serve as nature’s avian rodent population control, and in many parts of the world farmers rely on barn owls to control local rat populations. In one day, a barn owl will typically catch and eat one rat. In one year, a barn owl family of 3 or 4 owls can catch & eat up to one thousand or more rats. (Peregrine Fund) For farmers, local owl families serve as a bulwark against rats pilfering their crops, therefore protecting farmers’ livelihoods.

History of Rodenticide Usage

For hundreds, possibly thousands of years, humans have employed naturally occurring vertebrate pesticides (e.g. cyanide and strychnine) as a form of pest control. Rodenticides are and have been widely used in agricultural, urban, and suburban settings to control rodents that can damage crops, structures, and pose health risks to humans.

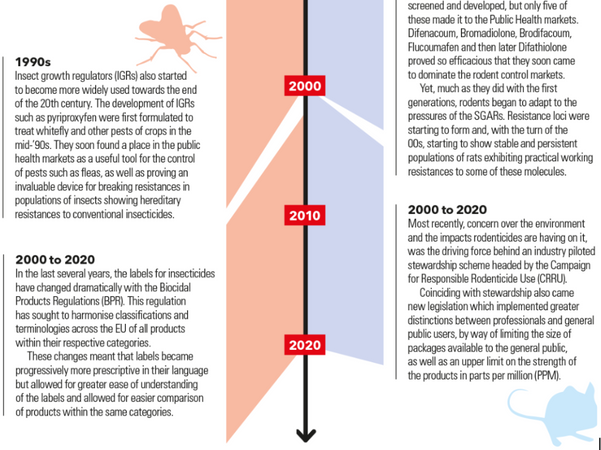

Brief Timeline

Between 1940 and 1990, research and development into new forms of rodenticide peaked: FGARs were developed in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, and SGARs were developed in the 1970s and 80s, partly to overcome resistance in target rodent populations. (Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee) The first FGAR, Warfarin, was introduced in 1947. (Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee) Commonly used FGARs include Warfarin, Chlorophacinone, Diphacinone, and Cholecalciferol. The second-generation anticoagulants were introduced to overcome resistance to the first-generation compounds, which was first observed in the late 1950s. (Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee). Commonly used SGARs include Brodifacoum, Strychnine, Bromadiolone, Difethialone, Bromethalin, and Zinc Phosphide (National Pesticide Information Center, 2016).

Rodent Resistance

Since FGARs take longer to neutralize rodents, some rodents had developed genetic resistance to FGARs, such as warfarin. The solution? SGARs. Unlike FGARs, which took at least 1 to 2 days to take effect, the effects of SGARs were noticeable within hours. Unfortunately, they also have lasting long-term effects (Science Direct, 2005).

Mechanism of Toxicity

Anticoagulant Rodenticides mainly affect organisms through vitamin K cycle inhibition, an essential cycle for blood clotting; rodenticides lead to uncontrolled internal/external bleeding, and ultimately death. FGARs must be consumed more than once to deliver a lethal dose; FGAR baits left out for a week or so usually do the job. On the other hand, SGARs act slowly; when consumed over the same time frame, the rodent will accumulate many times the lethal dose by the time it perishes, ensuring that whoever then consumes the rodent also consumes a debilitating and often lethal dose.

Owls are particularly vulnerable to secondary poisoning, which occurs when they consume the aforementioned poisoned prey, including rats, mice, and voles. Over time, owls may ingest multiple poisoned rodents, leading to poison bioaccumulation and increased toxicity/damaging effects to their bodies. (Rattner et al., 2014).

Owls feel pain. When they’re poisoned, their suffering is excruciating and their death is not without anguish.

Sublethal Effects

Chronic SGAR exposure induces sublethal effects into an owl’s system, blocking clotting factors in an owl’s body & weakening their immune system. This causes extensive suffering, reduced survival odds, reduced reproductive success, and increased disease susceptibility. In the case of Flaco, an owl who escaped captivity and lived free for over a year in New York, chronic SGAR exposure turned a virus that his body could normally handle into something his body could no longer adequately contend with, leading to his early grave. Flaco's fate isn't uncommon; any owl exposed to SGARs over long periods will likely suffer similar debilitating effects.

Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides are designed to kill rats slowly and painfully. Affected rats can survive for up to 10 days. During this time they can return to the bait station and ingest accumulating lethal doses. Weakened from internal bleeding, rodents are a toxic ticking bomb for any animal who preys on them.

and toxins remain in their bodies for up to 100 days.

In comparison, an owl will usually kill their prey instantly. Given that SGARs maximize suffering, while owls minimize suffering, which is the more humane way to kill a rodent?

Human Threat

Humans are the single greatest threat to owl populations.

Our vast array of synthetic materials & chemicals, combined with the quantity at which we use them, is not something nature’s natural cycles are prepared for.

Nothing in nature exists alone; all too often, anthropogenic poisons don’t affect the intended target without consequences for the rest of the food web.

As illustrated in the infographic to the right, owls can ingest rodenticides through contact with numerous rodent & non-target rodent and/or non-rodent organisms.

Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticide: ecological positive feedback loop

SGAR poisoning & resulting predator death creates a positive feedback loop. As more owls are poisoned and die, rodent populations can multiply unfettered at quicker rates. If there are more rodents and less owls to control rodent populations, more SGARs are required. This in turn will poison & kill owls at a quicker rate. The cycle, if unmitigated, could result in a complete extinction of some or all owl species in the coming decades.

Owls in Nature

What about owls in natural environments who don’t come into contact with urban/agricultural environments? They’ll be fine, right? Unfortunately not. Researchers in Australia collected dead tissue samples from owls in both urban environments & natural environments, and determined that most owls have rodenticide, specifically SGAR brodifacoum, in their systems across an urban-forest/agriculture gradient, suggesting widespread rodenticide exposure (Cooke et al., 2022). This study only provides evidence that Australian owls in natural environments are significantly exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides; further research is needed to assess natural landscapes worldwide.

How is widespread SGAR poisoning affecting owl populations?

In Europe, the Barn Owl Trust (BTO) has found a significant decline in the UK barn owl population, determining that an increased use of SGARs is the cause of this population decline (Barn Owl Trust, 2023). Furthermore, significant anticoagulant exposure has been determined in research from France, Spain, Scotland, Malaysia, and Taiwan (Gomez et al., 2022).

Research in North America has determined that rodenticide exposure is causing declines in several owl populations, including the Northern Spotted Owl and the Barred Owl (Elliott et al., 2016).

Moreover, a recent 2023 study conducted in Australia detected anticoagulant rodenticides in 92 % of nocturnal avian predators (Cooke et al., 2023).

Help Save the Powerful Owl from Rodenticide Poisoning

Harmful effects of SGARs on mother owls & their innocent owlets

As she regurgitates food for her young, a mother owl (or any bird of prey) with rodenticide buildup present in her system will unknowingly transfer chemical poison to her chicks. For example, when New York’s Pale Male (a beloved red-tailed hawk) mated again after losing his first mate to rodenticide poisoning, rodenticide sickened two of his chicks and possibly killed another. Mother owls in every environment are at risk of accidentally poisoning their beloved chicks.

An article by the Audubon Society writes that a four-year survey (1999 to 2003) by the Environmental Protection Agency found that at least 25,549 children under age six ingested enough rodenticide to suffer poisoning symptoms. Currently about 15,000 calls per year come in to the Centers for Disease Control from parents whose children have eaten rodenticides. Even if you place bait where children can’t get it, rodents are apt to distribute it around your house and property. Worse, according to data sourced from the EPA, children in low-income families are disproportionately exposed to rodenticides. Children are at risk.

The Moral Aspect

In an interview concerning the moral dilemma of how humans treat animals, moral philosopher Peter Singer states that he believes suffering is what unites all animals, including humans. Therefore, any barrier we differentiate ourselves by is purely artificial. We all feel pain and suffer, regardless of whether we have feathers or not.

To those with families: look at your children. Now look at a family of owls. Despite the differences, aren't your situations fundamentally similar?

You both want to provide ample food and a loving home for your family.

You want to keep your children out of harm's way as much as you can, because you (hopefully) want the best for them.

Like it or not, this planet isn't designed solely for human use or human benefit. We're one kind of animal among thousands of different species, and we too often choose harmful, unsustainable practices, instead of making decisions for the long-term benefit of the planet's ecosystems as a whole.

Rodenticides are not conducive to a sustainable future. What can we do about it?

<- SOLUTIONS ->

Remedying the harmful effects of widespread SGAR exposure in owls is not easy, nor is convincing the public of its importance. Although some people care about nature for nature’s sake, many people are more amenable to caring about nature when given incentives or reasons to care, especially when they understand the direct & indirect ways that nature affects their everyday life.

Realistically, rodenticide is unlikely to be completely phased out in the coming decades. Instead, rodenticide usage can be reduced and replaced with other anti-rodent measures. When the situation necessitates unavoidable rodenticide use, it can be rendered less harmful. A combination of large-scale regulative/restrictive measures and grassroots individual action is the ideal path. Here's why.

GLOBAL SOLUTION:

Rodenticide Regulation and Restriction, by Local and Federal Governments

Several governments, both local & federal, have taken steps to mitigate rodenticide-driven ecological harm experienced by owls. The British Columbian government, “in response to concerns over the effects on owls and other wildlife,” restricted the use of SGARs to essential services, stating that, “If you're not on the essential services list, you're not allowed to use these products” (Government of British Columbia). B.C. requires rodenticide usage to coincide with Integrated Pest Management policies, requires licensure for those not on the essential services list, and outlines strict rodenticide usage guidelines. Furthermore, who a vendor can sell to is regulated, and vendors must communicate guidelines for proper SGAR use to buyers.

Essential Services

Restrictions

Moreover, although the USA’s Environmental Protection Agency has implemented rodenticide regulations & restrictions, such as the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), some states follow the EPA guidelines without implementing additional restrictions, while others go above and beyond to protect owls from secondary poisoning.

Assembly Bill 1322 (California Ecosystems Protection Act of 2023)

California passed Assembly Bill 1322, which has significantly regulated & restricted rodenticide use. (California State Legislature AB1322) The bill entails:

-

Prohibition in Wildlife Habitats: The use of SGARs and diphacinone is prohibited in state parks, wildlife refuges, and conservancies unless specific exemptions apply.

-

Statewide Ban: The use of these rodenticides is banned across the state until certain conditions are met, including certification from relevant authorities. This minimizes careless rodenticide usage.

-

Exemptions: similar to British Columbia, this law provides exemptions for government agencies using rodenticide for public health, protecting water supply infrastructure, mosquito or disease vector control, eradicating invasive species on offshore islands, or protecting endangered species and their habitats.

-

PROPOSED California Assembly Bill 2552 would expand the existing temporary rodenticide ban to include FGARs such as chlorphacinone and warfarin. The state has laws restricting some rat poisons, but people, pets and wildlife continue to be harmed by them. "This bill offers additional safeguards from the most toxic rat poisons and provides a framework for state regulators to develop stronger restrictions for their use."

Although the Pacific Northwest’s lumber industry has declined as a result of federal intervention (the Endangered Species Act) setting aside forests for conservation purposes, trees don’t grow faster than humans use them. Assistant Professor Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago says that "had the logging continued as projected, the roughly 200-years-old forests those workers were cutting down would likely be gone today—and with them, the jobs” (University of Chicago News). Opponents of conservation often exaggerate the extent to which conservation costs us jobs, or opportunities. The costs are real, but fortunately they're manageable, and not infinite.

This circles back to a recurring conservation problem: either we spend a seemingly large sum of money now on preventative measures, or face a far greater price once a problem demands fixing.

The Endangered Species Act has been successful in preventing extinctions, but less successful at promoting species recovery. Either the ESA needs to be revised to further promote species recovery, or the preventative capabilities need to be expanded.

Social Media Advocacy

Raising awareness through social media requires, above all, an understanding of which sources are credible and which aren’t. Once individuals know where to get accurate information, they can easily spread awareness about their problem of choice. It’s as easy as searching for an issue of interest and exploring the connected accounts who post about that issue. I determined where to find the foundational information on current ornithological news that supported my platform by:

-

Exploration searches using keywords (birds, owls, owl issues, #ornithology, to name a few)

-

Researching/following credible ornithology-focused Twitter (X) accounts and reading through abstracts in scientific journals and scientific articles.

-

Observing how existing advocacy accounts formatted their posts and creating mine using theirs as a template. Straight to the point posts were most effective.

-

Adjusting my focus from broad (birds) to narrow (ecological impacts of rodenticide experienced by owls) as I learned more about my species through weeks of posting and writing.

Overall, I did everything using Twitter, Google searches, Google Docs, and an open mind. Therefore, anyone with access to these tools can make a difference like me.

INDIVIDUAL SOLUTION:

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

What is IPM, and how can individuals apply it to conserve and protect local owl populations?

The IPM strategy is ecosystem-based, focusing on long-term pest prevention through a combination of biological control, habitat manipulation, and modification of cultural practices.

Pesticides are a last resort that should be used only after monitoring indicates they are necessary according to established guidelines.

Pesticide use should only be done to remove the target organism.

Which pest control materials are used and how they're applied must minimize risks to human health, beneficial and nontarget organisms, and the environment.

This approach combines natural predation, natural rodent repellent, and human effort, creating a robust system for keeping rodents in check that relies on biological control measures rather than chemical control. Furthermore, IPM is a long-term solution; it keeps owls in mind at every step. Unfortunately, owls alone cannot control rodent populations, especially in urban areas.

We should take preventative measures such as sanitation (keeping structures clean), exclusion (sealing entry points to prevent rodent incursion), and structural modification (removing clutter, landscaping, etc.). Structures should be routinely monitored to keep track of IPM effectiveness, and any change in the infestation should be met with adequate adjustment. Individuals should prioritize biological controls (owls) and mechanical controls (snap traps) over chemical controls (rodenticides), which serve as a last resort. An easier step that many people can take is outlined below.

Artificial Nesting Boxes

In an increasingly urbanized world, owls are faced with less and less natural habitat options. Fortunately, anyone can build an artificial nest box to encourage small and medium-sized owls to move into the neighborhood and start a family. Larger owls prefer spacious open-air nests. Furthermore, rodents become less of a problem when owls live nearby, especially barn owls. By encouraging natural predators to control rodent populations, people are less inclined to use rodenticide against rats.

Above and Beyond:

Owl Wise Leader (OWL) Program

Grassroots solutions are an excellent way to mobilize a lot of people regardless of individual qualifications. One influential program motivates businesses or organizations to abstain from using rodenticides in order to send a message: owls will take care of the rodents if humans take care of the owls. Furthermore, O.W.L.s can share informative materials that describe the problem in simple terms to locals.

Those eligible to be O.W.L.s are:

-

businesses that stop selling rat poison products of any kind

-

pest control companies, homeowners’ associations, community groups, urban farms, municipalities and agencies, and others that stop using rat poison products of any kind

-

poison-free universities and other educational institutions (Raptors Are The Solution)

Compared to rodenticide, owls aren’t consistently effective rat control for large infestations.

Moreover, conservation is expensive. Why bother?

Opponents to owl conservation efforts claim that:

-

Resources spent on owl conservation are better spent on more pressing conservation issues that have a wider impact on biodiversity or social issues.

-

Conservation efforts have taken jobs from land-use industries, especially the Pacific Northwest’s lumber industry.

-

“What good is it trying to save an owl when the planet is dying?” (The Last Stand)

-

Every year, authorities spend more than $1 billion on recovery plans and habitat restoration for endangered species. At the same time, the list of endangered species continues to expand. (The Last Stand)

Owl conservation is mainly about protecting owl habitats & food sources. Protecting habitats means protecting forests, which are immense carbon reservoirs. Therefore, protecting owls means conserving/protecting old growth forests and biodiversity.

Benefits of Rodenticide Use

SGARs are guaranteed to kill target & non-target rodent species, as well as eliminating FGAR-resistant rodents. An owl isn’t guaranteed to kill an entire rat infestation, and may kill rats at a slower rate than they multiply. Although this makes SGARs extremely effective, it also guarantees a high probability of lethality for owls affected by secondary poisoning. If the owl(s) managing the rat infestation in question die, then the biological control has perished, and an individual now has to rely on mechanical controls or chemical controls. Any rats that escape may further contaminate the local ecosystem’s owl population.

Furthermore, due to their high effectiveness and potency, SGARs are particularly beneficial in controlling severe and/or established rodent infestations, where quick countermeasures are required. Severe infestations may multiply faster than owls can eat them, demanding either more owls or a quicker chemical solution. Regardless, for most problems, prevention is easier than remedification. IPM’s preventive measures combined with responsible monitoring & adjustment drastically reduces the likelihood of severe infestations. The more people care, the less likely a small infestation is to spiral out of control.

Overall, SGARs are great at killing ecosystems. They take care of the rat problem, but they also kill the owls. Without the owls, if/when another rodent infestation occurs later on, there’s less biological rodent control. Without owls to take care of this new infestation, chemical control (rodenticide) is in greater demand, therefore chemical companies will make more money without a care for the growing pile of owl corpses that they’re partly responsible for.

Now What?

After reading this, what is your vision of the world?

Do you want to chemically destroy ecosystems, support chemical corporations, and contribute to avoidable suffering in numerous owl species?

Or do you want to preserve biodiversity, keep this planet’s owls alive, and prevent rodent infestations before they reach the point that chemical intervention is necessary? The choice is yours.

Works Cited

INTRODUCTION

Clark, Christopher J. et al., “Great Gray Owls hunting voles under snow hover to defeat an acoustic mirage.” Proc. R. Soc. B.28920221164 23 November 2011, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2022.1164#d1e502

Clark, Christopher J., et al., “Introduction to the Symposium: Bio-Inspiration of Quiet Flight of Owls and Other Flying Animals: Recent Advances and Unanswered Questions “ Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 60, Issue 5, November 2020, Pages 1025–1035, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icaa128

Ackerman, Jennifer. "What an Owl Knows." Science Friday, 23 Sept. 2011, www.sciencefriday.com/segments/what-an-owl-knows-ackerman/.

"Owls - Owl Research Institute." Owl Research Institute, www.owlresearchinstitute.org/owls-1.

Published online 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz111

Mackenzie, Dana. "To Silence Wind Turbines, Engineers Are Studying Owl Wings." Smithsonian Magazine, 20 Feb. 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/silence-wind-turbines-engineers-are-studying-owl-wings-180974659/.

PROBLEM

Oster, Lauren. “What Flaco the Owl’s Death Teaches Us about Making Cities Safer for Birds.” Smithsonian.Com, Smithsonian Institution, 17 Apr. 2024, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-flaco-the-owls-death-teaches-us-about-making-cities-safer-for-birds-180984117/

Cooke, Raylene. et al. (2023). “Silent killers? The widespread exposure of predatory nocturnal birds to anticoagulant rodenticides.” Science of The Total Environment (2023), Volume 904, 2023, 166293,ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166293. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969723049185)

Conservation Letter: Raptors and Anticoagulant Rodenticides, Eres A. Gomez; Sofi Hindmarch; Jennifer A. Smith Journal of Raptor Research (2022) 56 (1): 147–153. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-20-122

Elliott, J. E. et al., (2016). "Exposure pathways of anticoagulant rodenticides to nontarget wildlife." Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188(10), 576.

Rattner et al., (2014). “Adverse Outcome Pathway and Risks of Anticoagulant Rodenticides to Predatory Wildlife” Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 48, no. 13, 2014, pp. 7515-7523. https://doi.org/10.1021/es501740n.

Image 1: Michigan Audubon. "Rodenticides Kill More Than Rodents." Michigan Audubon, 24 July 2019, https://www.michiganaudubon.org/rodenticides-kill-more-than-rodents/. Accessed 25 May 2024.

Image 2: Raptors Are The Solution. "Free Outreach Materials." Raptors Are The Solution, https://raptorsarethesolution.org/free-outreach-materials/#Barn%20Owl%20with%20Poison-Green%20Mouse. Accessed 25 May 2024.

The Peregrine Fund. "Common Barn Owl." The Peregrine Fund, https://peregrinefund.org/explore-raptors-species/owls/common-barn-owl. Accessed 25 May 2024.

National Pesticide Information Center. "Rodenticides." NPIC, Oregon State University, http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/rodenticides.html

"Infographic: A Short History of Public Health, Pesticides & Pest Control." BPCA, British Pest Control Association, https://bpca.org.uk/news-and-blog/infographic-a-short-history-of-public-health-pesticides-pest-control/259101. Accessed 26 May 2024.

"Rodenticide." ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/rodenticide. Accessed 26 May 2024.

"1st Generation Anticoagulants." RRAC Resistance Guide, Rodenticide Resistance Action Committee, https://guide.rrac.info/rodenticide-molecules/1st-generation-anticoagulants.html. Accessed 26 May 2024.

Konishi, Masakazu. "How the Owl Tracks Its Prey." American Scientist, vol. 61, no. 4, 1973, pp. 414-424. Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society, https://www.americanscientist.org/article/how-the-owl-tracks-its-prey.

SOLUTIONS

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. "Rodenticides." APVMA, https://www.apvma.gov.au/resources/chemicals-news/rodenticides. Accessed 1 June 2024.

California State Legislature. "Bill Text: CA AB1322 | 2023-2024 | Regular Session." LegiScan, https://legiscan.com/CA/text/AB1322/id/2840751. Accessed 1 June 2024.

Owl Research Institute. "Attracting Owls to Your Backyard." Owl Research Institute, https://www.owlresearchinstitute.org/attracting-owls-to-your-backyard. Accessed 1 June 2024.

Government of British Columbia. "Rodenticide Ban." Government of British Columbia, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/pesticides-pest-management/legislation-consultation/rodenticide-ban#list. Accessed 1 June 2024.

Wilen, Cheryl. “How to Manage Rodents Using Integrated Pest Management.” University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, 29 Oct. 2021, https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=51488. Accessed 2 June 2024.

"IPM in Communities." IPM Institute of North America, https://ipminstitute.org/what-is-ipm/#community. Accessed 2 June 2024.

Center for Biological Diversity. "California Wildlife Bill to Tighten Rat Poison Restrictions." Center for Biological Diversity, 14 Feb. 2024, https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/california-wildlife-bill-to-tighten-rat-poison-restrictions-2024-02-14/. Accessed 2 June 2024.

6 Home Remedies to Repel Mice and Rats." PuroClean, https://www.purcorpest.com/blog/6-home-remedies-to-repel-mice-and-rats/#:~:text=Essential%20oils%20that%20may%20be,you%20see%20traces%20of%20rodents. Accessed 2 June 2024.

Schroeder, Audra. "The Internet Has a Rat Poison Problem." Audubon, Winter 2021, https://www.audubon.org/magazine/winter-2021/the-internet-has-rat-poison-problem. Accessed 2 June 2024.

"Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and Federal Facilities." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/federal-insecticide-fungicide-and-rodenticide-act-fifra-and-federal-facilities. Accessed 2 June 2024.

Ferris, Ann, and Eyal Frank. "Labor Market Impacts of Land Protection: The Northern Spotted Owl." Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, vol. 107, 2021, 102421. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0095069621000589.

Wagner, Eric. "The Last Stand." Earth Island Journal, Spring 2014, https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/the_last_stand/.

Lundquist, Laura. "Poisons Used to Kill Rodents Have Safer Alternatives." Audubon Magazine, Jan.-Feb. 2013, https://www.audubon.org/magazine/january-february-2013/poisons-used-kill-rodents-have-safer.

University of Chicago News. "Northern Spotted Owls: Conservation, Timber, Jobs, and the Endangered Species Act." University of Chicago, Publication Date, news.uchicago.edu/story/northern-spotted-owls-conservation-timber-jobs-endangered-species-act.